This sermon is for Thanksgiving Day (November 23). It could also be used for a pre- or post-Thanksgiving worship service. Scripture readings: Deut. 8:7-18; Ps. 65 2 Cor. 9:6-15; Luke 17:11-19 Sermon by Josh McDonald from Luke 17:11-19

Double Stranger—Double Grateful

Introduction

In Luke 17:11 we find Jesus, on his way to Jerusalem, traveling along the border between Samaria and his home area of Galilee (see the map below). This means he was journeying in what was considered “no-man’s land,” for Samaritans and Jews went out of their way to avoid contact (for the history of this rift, click here).

The Samaritans were descendants of the Israelites left in the land when most of their kinsmen in the Northern Kingdom were deported by the Assyrians some 700 years before Christ. Many of those left behind intermarried with gentiles, yielding a mixed group known as the “Samaritans.” Many of them practiced their own brand of Judaism. The Jews of Jesus’ day derisively referred to them as “dogs,” considering them to be half-breeds and heretics. The Samaritans returned the favor, holding deep animosity toward the Jews.

Liminal space

So here is Jesus walking the back trails in the no-man’s land with Galilee stretching to the north and Samaria to the south—a rather wild, untended place. It was the kind of place anthropologists refer to today as liminal space (with the word “liminal” derived from the Latin word limens, meaning threshold).

A liminal space is the in-between space where a person in a culture is moving between two stages or two places in life. For example, a teen inhabits a liminal space—not quite a child, not quite an adult. An adult in midlife crisis inhabits a liminal space—not quite young, not quite old. A comedian once noted that we reach this mid-life liminal space at about age 40 when we’re not young enough for anyone to be proud of us, and we’re not old enough for anyone to want to help us. After all, no Boy Scout ever talked about helping a 40-year-old across the street!

So that’s liminal space—not quite this, not quite that. Liminal space is about the awkward often painful time of transition that calls one’s identity into question. And here is Jesus in a sort of liminal space—not quite at home, not quite completely removed from the familiar. We’re reminded of Jesus’ statement: “The Son of Man has no place to lay his head.” So here Jesus is, and here he meets a group of people who, like him, are wandering.

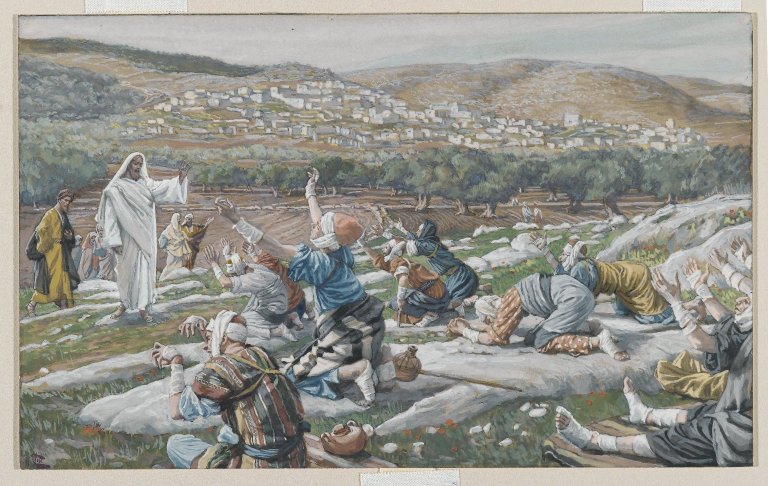

Jesus and the ten lepers

As Jesus heads into a village, he is met by ten lepers. They stand at a distance and call out to him in a loud voice, “Jesus, Master, have pity on us!” The term “leper” in that day referred to people suffering various skin diseases including bad eczema, cellulitis and actual leprosy. People with these diseases were required to wear torn clothing and announce themselves by crying out, “Unclean! Unclean!” in order to protect others from infection. Until they got better, lepers were excluded from temple life, considered to be both physically and ritually impure.

Some lepers did recover from the less serious skin disorders, and there were special rules in the book of Leviticus as to how they could then be restored to the temple and thus to the community. However, those who had full-blown leprosy never did recover and so were consigned to a life of living in exile—a life in liminal space, kept outside of populated areas: not quite this, not quite that. People without a country.

It is often on these side trips—on back trails in liminal spaces—that the Lord meets us. When we’re out of our routines—out of our comfort zones. Sometimes it’s only when we’re in these no-man’s lands and times that we are able to fully listen to God.

But this is where Jesus often hangs out. When we’re vying for attention or in hot pursuit of a career, or obsessing about our own status and ego—we’re just a little too busy for him. We’re already occupied, no need to listen to God, we’re chasing mirages.

This group of lepers is under no such illusion—at least at that moment. They have been driven from family and community life. There was not only a fear of getting whatever they had, there was the assumption that they had been cursed by God for some sin. And now in the distance, these accursed ones see a Rabbi known to be a healer. So, at a proper distance, they call out in a loud voice: “Jesus, Master, have pity on us!” By law, this is what they are required to do. They have to warn everyone that they are unclean to keep you at a distance. You can’t get close enough to them to have a conversation. But Jesus hears the desperation in their voices.

Have you ever come to God out of that kind of poverty, that sort of desperation? It’s when we’re in liminal places like that, that Jesus really gets to work with us. Why? Because we’re ready for his help, his healing.

When Jesus saw these ten lepers approaching, he said to them: “Go, show yourselves to the priests.” And as they went, they were cleansed.

Jesus was sending them to get the routine check-over from the priests as prescribed in the book of Leviticus. This may seem strange to us. Didn’t Jesus fulfill the law and therefore such ceremonies are no longer needed? Remember, Jesus has broken the Sabbath and forgiven sins apart from the rituals of the law, thus undercutting the temple system at its root. So why does Jesus now tell these lepers to obey the law’s rituals?

I think it’s because Jesus is thinking of their future well-being. If they don’t go through these rituals, they will be excluded from temple life, which means they will be excluded from the center of their culture. Seeing family, connecting with their heritage, let alone getting a job or making connections will never happen unless they go through the proper temple rituals. So Jesus’ concern for them is very practical, though I think it also points to something much deeper.

The story goes on to tell that the cleansed lepers return to their lives and 90% of them never come back to thank Jesus for healing them. This is an interesting commentary on the topic of thankfulness. Jesus gives them an “out” from the liminal space they are trapped in to return to the safety and security and identity of their former lives. It involved going back to the temple, to there be reinstated, to get back to things as they always had been. Essentially acting as though nothing had happened.

How easy it is for us to forget to be thankful! Perhaps we’re praying for something and God answers, yet the “gnat-like cloud” of concerns and distractions of life keep us from responding to God in thanks. As one commentator said, “Thankfulness is not a command, it’s an invitation.” It’s easy to drown out the voice of God in our lives and come back into business as usual, never changed.

There’s a story of a businessman running late for a meeting. The meeting was vitally important, and he realized he couldn’t find parking. If he was late, it would mean big losses for him. Not a religious man, this crisis pushed him even to the point of prayer. He promised God that he would straighten up and fly right and even come to church if God would just make a parking spot appear for him. He even promised that he would give half his profits to the church! Then he turned the corner and there was a parking space! Then he said, “Oh, never mind God, I found a space!”

Isn’t this easy to do? Just run back into the fray as if we were never in need, as if we were never hurting and had not received God’s healing. Thankfulness is not a command, it’s an invitation. Never mind, I found a space. Never mind, I was healing anyway. Never mind, I was able to save myself or find fulfillment, or make peace on my own.

But one of the ten lepers wakes up and sees what is going on. Sadly, the other nine just kept moving. The one leper somehow understands the great treasure he has received from Jesus and returns to give him thanks.

As English theologian GK Chesterton said, the world is a sort of cosmic shipwreck. A person in search of meaning in this world resembles a sailor who awakens from a deep sleep and discovers treasure strewn about, relics from a civilization he can barely remember. One by one he picks up the relics—gold coins, a compass, fine clothing—and tries to discern their meaning. Fallen humanity is in such a state. The good things of earth—beauty, love, joy—still bear traces of their original purpose, but amnesia mars the image of God in us.

Gratefulness is part of restoring that image. It’s part of waking up to the reality of who God is and thus who we are. Gratitude gives dimension to everything in our lives. By being grateful we become aware that everything is a gift. As one of the great Greek thinkers said, “It is not what we have, but what we enjoy that constitutes our abundance.” Sadly, as fallen beings, we enjoy abundance—we eat and drink and amass wealth, and yet it is never enough.

An interesting aside here. There was a 19-year-old garbage man in England named Michael Carrol. He won about $14 ½ million in the lottery. He spent it within a few years on a mansion, several cars to have demolition derbies on the lawn, crack cocaine and prostitutes. Within a few years, he was on unemployment living in the woods in a tent. He now works in a factory somewhere, knowing that he would have been dead if he hadn’t been stopped by running out of money. There was never enough. Always more and more. Simply having all this stuff didn’t raise him from being a petty thief who was going nowhere with his life—it just raised the amount of damage he could do.

It’s not what we have, but what we enjoy that constitutes our abundance. Even if we “have all we want” it’s worth nothing if we don’t take joy in it. Gratitude has a key part to play in truly enjoying what we have. Through the practice of gratitude, we awaken like the stranded sailor, beginning to remember who we truly are, what life can truly be, whose image we truly bear.

When was the last time we were thankful for something we get every day? When was the last time “we saw we were healed,” like the one leper who took a second look and understanding the source of his healing, returned to Jesus and, as it says in v. 16, “Threw himself at Jesus’ feet and thanked him.”

The double stranger

Now note what else is said of that leper: “He was a Samaritan.” Truly shocking; doubly amazing. He was a double stranger—both a leper and a Samaritan. Not only would his disease exclude him from the community, his ethnicity made him despised by the Jews. People thought of his leprosy as a curse for his sin, and they thought of him as a cursed person already because of his heritage. He is thus the double stranger—the double other. Yet he is the one who returns to thank and praise Jesus.

Sometimes the double stranger is the only one who truly understands. The rest of us are so caught up in the swarm of life’s distractions that we don’t see what God is up to. I heard one pastor say, “We must linger in gratitude.” It’s hard to do that—especially when there’s a Facebook feed to check, or election results to worry about, or other pressing things we just must attend to!

The Samaritan, former leper walks away from the pull of everyday life to linger with Christ. To linger in gratitude. Luke uses the word eucharisteo to describe his gratitude. This is the word used to describe how Jesus prayed over the bread and wine at the last supper—the word from which we get “eucharist,” one of the words we use to speak of the Lord’s Supper or communion.

What about us?

How hard is it to just sit and praise—to just sit and linger in gratitude toward God? Even this one hour and a half on Sunday, my mind chatters away with petty concerns. All this strange décor in here, that many of us aren’t used to, has its place. This reminds us that this place is special. There isn’t a practical use for this ornamentation and art, but it is meant to remind us to linger. To step out of the current of everyday life for a while—to be grateful and to worship.

Paul tells us in 1 Thessalonians 5:18 to “thankful in all things.” It’s interesting that he says “in” all things, not “for” all things. Jesus didn’t tell the “double stranger” to be thankful for leprosy. We can’t thank God for all the circumstances that have ever happened to us, but we can thank him “in” all circumstances. That’s part of the deal here—practicing aggressive gratitude even in the hardest of times.

When you can’t be here in the physical sanctuary, you can be in the sanctuary in your soul that you and God have built through the practices of gratitude, prayer and stillness. Our faith is not a change of circumstances, but a change of perspective on our circumstances. Because we know how the story ends—we know who’s in charge and who lovingly holds us in the palms of his hand. We know who is the beginning and the end—the alpha and the omega.

Affirming our humanity

Jesus asked, “Were not all ten cleansed? Where are the other nine? Has no one returned to give praise to God except this foreigner?” At first blush, this statement seems a bit harsh, calling the man the name that others call him—foreigner. What Jesus is actually doing is contrasting the man with his cultured, non-foreign despisers. He is turning their own bigoted slurs against them. He is, in essence, saying to them, “Even this one who you would call an outsider—a double outsider—a “foreigner” gets it and you don’t! His heart is softer toward God than yours; he understands and you don’t. Shame on you!”

Who is the double stranger in our community? Who are those that are outside of the outside? Notice that Jesus never approves of this man’s religious beliefs—he is not endorsing this man’s Samaritan religion. However, he is endorsing this man’s faith along with this basic humanity and in doing so he reaches out to him with healing.

Jesus has a way of showing up in those liminal spaces where so-called “rejects” reside—those who society has pushed to the margins, left to wander on their own. What if this Samaritan had been a mentally ill person? A homeless person who stunk of liquor and the filth of the streets? A gay or transsexual person? Jesus doesn’t affirm the Samaritan’s lifestyle but he did affirm that the man, like all humans, was beloved of God. In that way, Jesus affirmed his humanity.

Then Jesus says to the now-healed Samaritan, “Rise and go; your faith has made you well.” “Made you well”—a phrase that can mean being made well or whole, being saved, being healed. Did you notice that it is not those with “enough faith” who are healed? The others, who showed no actions of faith, presumably were also healed.

Jesus is talking on several levels here. Not only was the Samaritan’s body healed, so was his place in the community. There also seemed to be a healing deep within his own heart. He went from blessing to relationship—from physical healing to spiritual healing. He gained an entirely new perspective—jumping out of a plain old life to be grateful, and therefore to experience the greater life that is ours in a relationship of faith with Christ. He has not just received, but he has also given. That’s the essence of a relationship—not just unilateral action, but reciprocal action, of giving a response to what we are given.

Conclusion

The message here is about being thankful IN every circumstance no matter what it may be—no matter how we might, at first, feel about it. Being thankful in all circumstances declares that we know what our true identity is, who our true Lord is, and how the story ends. We know who and what truly matters.

The double stranger in our reading today was double grateful. In the end, we’re also double strangers—dwelling in liminal spaces, begging for mercy. This holiday season, which traditionally begins with Thanksgiving, ironically can be the most distracting and least relaxing time of the year. Let’s commit to taking some time apart from the shopping, cooking and gathering to return to our Lord, to fall down before him in praise, and thank him for who he is and for all he has, is and will yet do not only for our salvation, but for the salvation of all.

Happy Thanksgiving!

Please note that comments are moderated. Your comment will not appear until it is reviewed.